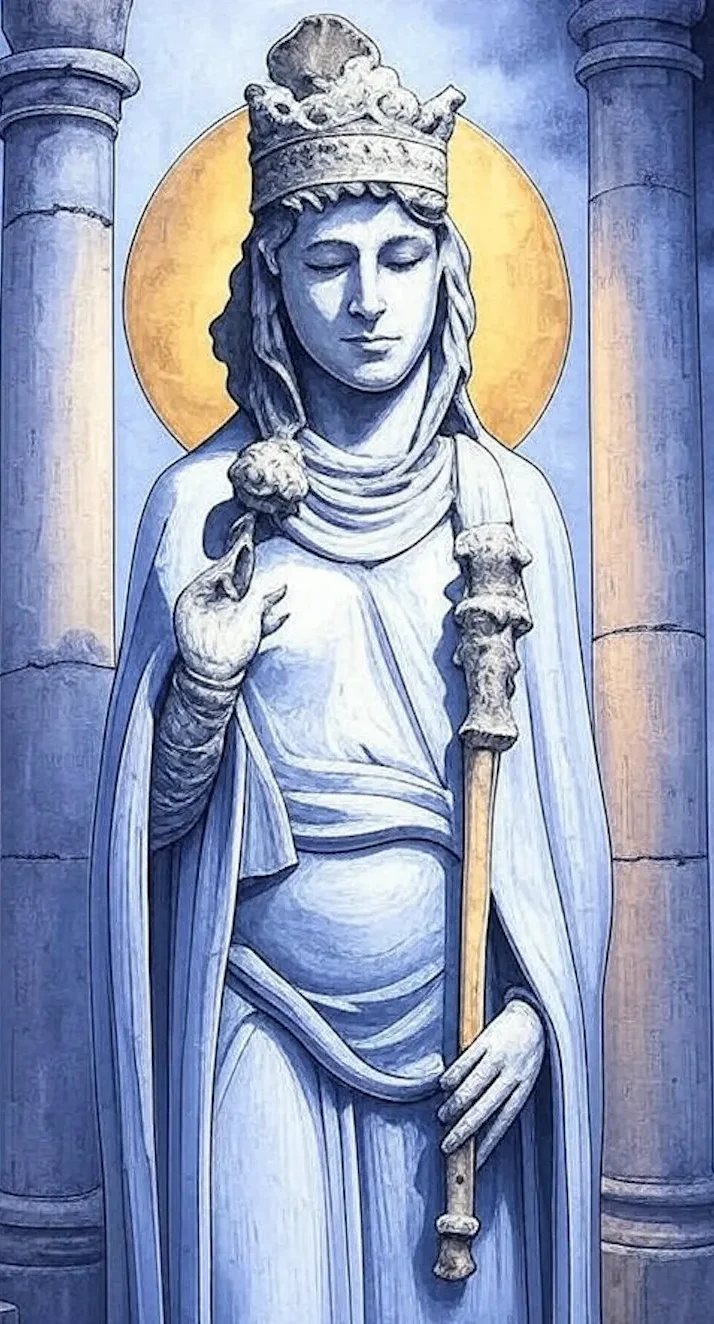

Leadership in a Global Digital Era Modelled on an Early Woman Ruler, The Queen of Sheba

Dr. Hana Al-Bannay

Over the years, numerous research studies have explored women's leadership [1]. Some scholars identify social and cultural barriers to women's leadership, while others compare women's leadership patterns to men's [2]. Studying women's leadership is complex, as women's experiences are shaped by multiple factors, including gender, ethnicity, race, socio-economic status, and age [2]. Despite women's accomplishments and merit to lead, men continue to outnumber women in leadership positions across all industries [3]. This phenomenon has united experts from disciplines such as social justice, feminism, gender studies, psychology, and cultural studies with leadership scholars to discuss and uncover institutional and sociocultural obstacles to women's right to lead [4]. In this article, I seek to highlight the relevance of feminine traits in global leadership in the age of digitalization and identify a potential knowledge gap due to limited studies on early female leaders.

What is a Woman?

A woman, an adult female human, is biologically distinct from a man [5]. These physiological differences, referred to as sex differences, arise from hormonal secretions and genetic effects. Evidence shows that men and women differ in brain activity, cognitive functions, and behavioral traits [6]. Although biological differences influence men's and women's behavioral aspects, social and environmental factors—such as physical activity, diet, socio-economic status, and education—modulate gene expression and contribute to developing psychosocial, gender-specific traits, self-perceptions, lifestyles, and experiences [7]. However, most human brains overlap and do not strictly categorize into male or female characteristics [6].

Throughout human evolution, women's biological traits have influenced their traditional roles as mothers, caregivers, and homemakers [8]. Within these social roles, and compared to men, women have developed and excelled in capacities such as interpersonal communication, empathy, resilience, multitasking, flexibility, and teamwork [9]. Men, conversely, have outperformed women in spatial reasoning, risk-taking, competition, mechanical and technical aptitude, and physical strength, aligning with their roles as providers, protectors, and decision-makers outside the home [10].

Within households, women have historically led in domestic, non-competitive environments [11]. They have utilized interpersonal skills to manage family relationships, forming collaborative teams. They practiced empathy and resilience in tending to the needs of children, the sick, and the elderly [8]. Their multitasking and flexibility skills were reflected in their multiple roles as wives, mothers, caregivers, teachers, and homemakers. Excluded from public spheres and household income generation, women were largely absent from leadership roles in the male-dominated social hierarchy [12].

Historical and Sociocultural Influences on Women's Status

Women's traditional roles were essential for creating societies and maintaining communities [13]. Historical analysis of early civilizations shows that women's roles were not always undervalued due to their economic exclusion. In pre-civilized societies, women had autonomy, and their roles were esteemed [14]. However, the decline in women's status was gradual, coinciding with urbanization, social stratification, and centralized power that favored male elites [13]. Men's contributions were perceived as more significant in economic development, elevating their social status across global communities [14].

With the development of economic systems and the establishment of written laws based on hierarchy, women became marginalized and subjected to male authority [13]. The egalitarian laws of pre-civilized societies transformed into norms favoring male dominance. A woman became "less than" a man. Alongside ethnicity, race, and socio-economic status, a woman's physiology became another marker of inferiority within the social hierarchy [8].

Throughout history, voices have risen in attempts to reform women's status, challenging social structures and cultural norms. Philosophers like Plato (380 BCE) argued that women could receive equal education to men, enabling them to lead [15]. Early Christianity (1st–4th century) advocated for women's spiritual equality, opposing Roman patriarchal views and uplifting women's status [16]. Similarly, Prophet Muhammad abolished slavery, including the ownership of women, and introduced women's equal rights in education, marriage, divorce, inheritance, respect, and social and political participation [17]. In the patriarchal Arab society, where the birth of a girl was considered shameful and newborn females were sometimes buried alive, he treated his only daughter, the mother of his lineage, with profound respect and affection, modeling women's entitlement to autonomy, social recognition, and spiritual equality [17]. Nevertheless, patriarchal attitudes and unequal treatment of women persist in many Muslim communities today [18]. These historical shifts in women's status provide a foundation for understanding their leadership styles and contributions.

Women's Leadership Styles

Scientific evidence provides mixed results on how women lead. Some studies suggest that women's leadership is distinctive, characterized by inclusive, collaborative, participatory, and nurturing approaches that create egalitarian work environments [12]. This perspective aligns with the skills women mastered in domestic leadership. Women tend to develop interpersonal relationships with subordinates, mirroring their communication aptitude [19]. Other sources indicate that women's leadership, compared to men's, is more driven by a motivation to help others and engage in personal, caring communication [2]. Transformational leadership is often observed in women leaders who employ empathy, individual consideration, and teamwork, referred to as "the ethic of care" [4].

Men, on the other hand, tend to adopt assertive, dominant, decisive, risk-taking, emotionally reserved, and hierarchy-attuned leadership strategies, shaped by the biology of masculinity, pre-civilization adaptations, and sociocultural gender norms [10]. Despite these differences, research reveals no significant gender-based disparity in leadership outcomes [12].

These leadership styles, particularly the feminine traits of empathy and collaboration, are increasingly relevant in today's interconnected and dynamic global landscape [19].

Leadership in the Age of Digital Globalization

A leader inspires, guides, and empowers others [20]. Recent reports on global leadership suggest that effective leaders must be versatile and adaptive to an "unpredictable, ever-changing digital environment" [21]. This drives the need for humanizing leadership, where leaders connect with team members, form personalized relationships, address their needs, and promote their well-being [19]. Key skills for humanistic leadership include empathetic communication, high emotional and social intelligence, conflict management, and promoting diversity and inclusion—all feminine leadership traits [4].

Digital globalization connects world cultures, navigating international boundaries to exchange knowledge and services across diverse sociocultural contexts [22]. Recent reports indicate that leaders with high cross-cultural awareness can improve team performance [23]. Research shows that both women and men follow international affairs and politics; however, women tend to prioritize global health and human rights, while men lean toward geopolitics and global issues [2]. These gender-based differences may reflect women's historical exclusion from public matters and echo their leadership focus on "the ethic of care" [4].

Feminine traits are critical in global leadership. A global mindset is essential in digital globalization [23]. While both men and women can possess cultural intelligence, women's global interests may differ from men's [2]. Although women exhibit distinct leadership styles, their effectiveness parallels that of men [12]. Sociocultural influences and environmental factors, both in constant flux, may produce overlapping gender traits [7].

To understand how these feminine leadership traits have manifested historically, examining an early woman leader offers valuable insights into their global relevance.

A Historical Cross-Cultural Model of Women's Leadership

Historical narratives may diverge from scientific generalizations [24]. Investigating the nuances of human lives within cultural contexts is a sophisticated process and may not yield universal conclusions. A myriad of factors can intervene in the interplay of human experiences in a social setting during a specific period [24]. Analyzing these variables through modern scientific lenses may not produce universal insights. For example, data on systematic and social barriers to women's leadership in modern times may not align with the contexts of early women leaders.

In ancient civilizations, following the establishment of economies and written laws, some women emerged as rulers and priests, demonstrating effective leadership [25]. Balqees[^1], for instance, was a prominent historical figure mentioned in the Qur'an, the Bible, Jewish and Ethiopian narratives, and various historical, archaeological, and cultural sources [17]. She was the queen of Saba (Sheba), an economic trade power in South Arabia (modern-day Yemen), around the 10th century BCE.

The Qur'anic narrative portrays Balqees positively. The story begins with Solomon receiving news that the people of Saba, led by a woman with a magnificent throne, worship the sun. Intrigued, Solomon sends a letter inviting Balqees to embrace monotheism. Upon receiving the message, Balqees consults her advisors, who suggest war. Instead, she opts for diplomacy, sending lavish gifts to test Solomon's intentions. Solomon, a prophet and king, rejects her gifts and worldly wealth. Balqees visits his kingdom, where she is amazed by his wisdom, power, and devotion, ultimately accepting his faith [17]. Balqees exemplifies an exceptional female leader—powerful, wise, and just—who inspired unity, loyalty, and respect among her people [25].

Balqees inherited the kingdom of Saba from her father and restored the Marib Dam, leading to prosperity, security, and stability [17]. She possessed intellectual confidence, emotional intelligence, effective interpersonal communication, and cross-cultural awareness [23]. Her leadership model aligns with transformational and situational styles [20]. She employed collaborative decision-making when receiving Solomon's letter, carefully analyzing its message. She avoided escalation, responding strategically with diplomacy [25]. Her visit to Solomon demonstrated openness to intercultural encounters and respect for different cultural customs in Jerusalem [23]. Power and pride did not cloud her intellectual reasoning. Accepting Solomon's faith while retaining her authority as queen showcased her ability to balance openness, humility, and assertiveness [17]. She transformed a potential threat from a foreign rival, Solomon, into rapport, trust, and unity [20]. Finally, she adapted her leadership strategy in Jerusalem and later embraced a new religious view, transforming the lives of her followers in Saba [25].

Balqees' transformational leadership was distinctly feminine, characterized by wisdom, self-discipline, and remarkable cross-cultural skills—essential for global leadership [23]. Her example underscores the timeless relevance of these traits in overcoming barriers and fostering unity.

Conclusion

Women are equal to men in their humanity. The development of economies and the exclusion of women from public affairs during early civilizations has led to a social hierarchy favoring male dominance. However, evidence highlights accounts that challenge the categorization of women's biology as inferior. Feminine traits are confirmed as significant in global leadership.

Early women leaders like Queen Balqees provide compelling case studies on overcoming social and cultural barriers, demonstrating global leadership skills, and addressing knowledge gaps due to the limited amount of research on historical female leaders.

[^1]: Also known as Bilqis or the Queen of Sheba in various historical and religious traditions.

Date: April 17th, 2025

---

References

1. Ridgeway, C. L. (2001). Gender, status, and leadership. Journal of Social Issues, 57 (4), 637–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00233

2. Hoyt, C. L., & Murphy, S. E. (2016). Managing to clear the air: Stereotype threat, women, and leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 27 (3), 387–399.

3. Catalyst. (2023). Women in leadership: Quick take. Retrieved from https://www.catalyst.org

4. Eagly, A. H., & Heilman, M. E. (2016). Gender and leadership: Introduction to the special issue. Leadership Quarterly, 27(3), 349–353.

5. Fine, C. (2017). Testosterone rex: Myths of sex, science, and society. W. W. Norton & Company.

6. Joel, D., Berman, Z., Tavor, I., Wexler, N., Gaber, O., Stein, Y., ... & Assaf, Y. (2015). Sex beyond the genitalia: The human brain mosaic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(50), 15468–15473.

7. Hyde, J. S. (2016). Sex and cognition: Gender and cognitive functions. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 38, 53–56.

8. Hrdy, S. B. (2009). Mothers and others: The evolutionary origins of mutual understanding. Harvard University Press.

9. Berenbaum, S. A., Blakemore, J. E. O., & Beltz, A. M. (2018). A role for biology in gender-related behavior. Sex Roles, 78(9-10), 676–691.

10. Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (2013). The nature–nurture debates: 25 years of challenges in understanding the psychology of gender. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(3), 340–357.

11. Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2021). The social psychology of gender: How power and intimacy shape gender relations. Guilford Press.

12. Eagly, A. H., & Carli, L. L. (2018). Through the labyrinth: The truth about how women become leaders. Harvard Business Press.

13. Lerner, G. (1986). The creation of patriarchy. Oxford University Press.

14. Ehrenberg, M. (2021). Women in prehistory. University of Oklahoma Press.

15. Tuana, N. (2018). Women and the history of philosophy. Paragon House.

16. Clark, E. A. (2020). Women in the early church. Liturgical Press.

17. Ahmed, L. (2019). Women and gender in Islam: Historical roots of a modern debate. Yale University Press.

18. Mernissi, F. (2011). Beyond the veil: Male-female dynamics in modern Muslim society. Saqi Books.

19. Goleman, D. (2020). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. Bantam.

20. Northouse, P. G. (2021). Leadership: Theory and practice. SAGE Publications.

21. Schwab, K. (2023). The fourth industrial revolution. Crown Business.

22. Friedman, T. L. (2022). The world is flat: A brief history of the twenty-first century. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

23. Livermore, D. (2021). Leading with cultural intelligence: The real secret to success. AMACOM.

24. Scott, J. W. (2020). Gender and the politics of history. Columbia University Press.

25. Cooney, K. (2021). When women ruled the world: Six queens of Egypt. National Geographic.

© Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.