The Spiral of Silence Restraining Inclusive Representation within Cultural Globalization

Dr. Hana Al-Bannay

Globalization and Mass Media in a Cross-Cultural Context

Globalization has increased cultural exchange, whereby world societies are becoming more interconnected. Advanced communications technology, emanating from the West, serves as a medium to share and deliver cultural practices and the latest social trends. World societies are gradually blending to form a hybrid, homogenized culture with a Western prevalence. English, for example, has become the leading global language of communication in both business and education. Additionally, mass media, delivering information through news and entertainment via various outlets such as the internet, social media, music and movies, has played a significant role in shaping world public views, attitudes, and behaviors. In this way, global social movements moulded by Western cultural contexts have transcended the diversity of world social traditions, norms, and rituals. While globalization can potentially foster inclusive and positive cross-cultural interactions, it can also perpetuate stereotypes due to oversimplification and misrepresentation of world societies.

Scholarly evidence shows that the global monopoly of Western media has contributed to spreading and enforcing stereotypes. This is partly due to historical colonization, which aimed to maintain power dynamics and the supremacy of Western imperialism. Moreover, with the motivation of increasing audience interest, global media may convey inaccurate, exaggerated, extreme, or shocking images of non-Western cultures. Critics have pointed out that Western media often overlooks and diminishes the complexities of global cultures, leading to overgeneralization and inferring that Western cultures are the aspirational standard. Distorted representations of people of color in Western media often portray them as exotic, mysterious, primitive, outdated, violent, or radical ‘others’ who come from a ‘foreign world’ that is either feared or romanticized. Women from those cultures are largely depicted as helpless victims, oppressed, or subservient, needing to be rescued. Muslim women, for instance, are often portrayed as submissive, passive, sexually repressed, and having little control over their lives. They are depicted as wearing modest clothing, such as the hijab or niqab, because they are subjected to the power of their male counterparts. These depictions are narrow, excluding personal choice and autonomy, lacking understanding of faith and culture, and ignore diversity. They therefore fail to present the social realities of Muslim cultures.

The media's stereotypical images have penetrated people's perceptions of cultural sensitivity. In my cross-cultural experiences, I have encountered personal interactions that reflected preconceived images that people had of me, which I did not identify with. My personal traits were sometimes misinterpreted through media stereotypes. For example, calmness and politeness were viewed as disempowerment or submission and voicelessness. Although those assumptions could be relevant in male-dominant situations in my home culture, the categorical lenses of Muslim women in Western media have impacted my cross-cultural interactions.

Social norms and values within diverse contexts constitute cross-cultural variations. In the Arab Muslim culture where I grew up, parents, elders, and teachers are considered worthy authority figures deserving of respect. Respect in this context implies politeness, appreciation, and speaking with a lower voice or calmness. I was fortunate that my experience of respect during my school years was reciprocal. My schoolteachers appreciated my dedication and commitment, in addition to my performance. In my home culture, silence or speaking less can symbolize good manners, respect, politeness, and wisdom. However, these social expressions of those values do not parallel across cultures. Coupled with media stereotypes, lacking awareness of the complexity of cultural variations can lead to inappropriate and/or patronizing cross-cultural interactions.

Cultures evolve and may induce intra- and inter-cultural differences over time. Social norms, values, beliefs, and behaviors may alter when they are passed from one generation to another or when they overreach distant geographical locations. Saint Mary is an example of a shared historical figure in varying cultural contexts in both Muslim and Western cultures. In Islamic traditions, she is considered an exceptional role model socially and spiritually, one of the four greatest women. The Quranic narrative of the story of Mary represents her as an iconic female who defied the challenges of patriarchy and stood out as a symbol of gender equality in terms of spirituality and social status. Saint Mary is highly revered as a model for Muslim women, who aspire to the qualities she had, such as piety, devotion, courage, resilience, and purity.

According to the Quran, when Mary’s mother was pregnant, she vowed to place the child in the service of God. Although girls were not expected to have a role in the temple, this mother fulfilled her promise. Mary grew up in the temple under the care of Prophet Zachariah. When she reached adulthood, the Virgin Mary miraculously gave birth to Prophet Jesus. She bravely returned to her community despite accusations that she had committed an immoral act. To defend herself, Mary was instructed by God to stay quiet and point to the baby, who spoke from the cradle, declaring himself as the messenger and servant of God.

In both Muslim and Western cultures, Mary is depicted in modest clothing. Modesty is considered a virtue in both cultures; however, it is defined and applied very differently. In Muslim societies, modesty in behavior and dress is considered a religious virtue to which both men and women are expected to conform. Adopting Mary’s behavioral model, Muslim women may wear modest clothing or a hijab to express their faith and dignity, or they may seek to focus attention towards their character, by oposing the commercilization of their bodies. Muslim women may view the hijab as empowering, especially when they demonstrate their equality to men’s capabilities with less attention to their physical appearance. Western individual freedom intersects with secular views of personal choice, which have resulted in diverse modes of expressing modesty. In the West, modesty in clothing is more individualistic and not necessarily tied to religion. It is often observed in professional settings. In this respect, Western media does not account for cross-cultural variations, aligning with an ethnocentric orientation. Not only does it ignore Muslim women’s agency, perspectives, and social contexts, but it also silences the voices of the majority of Muslim women and reinforces a selective image that is accepted as a reality among Western viewers. This process can be explained within the theory of the Spiral of Silence.

The Spiral of Silence: An Overview

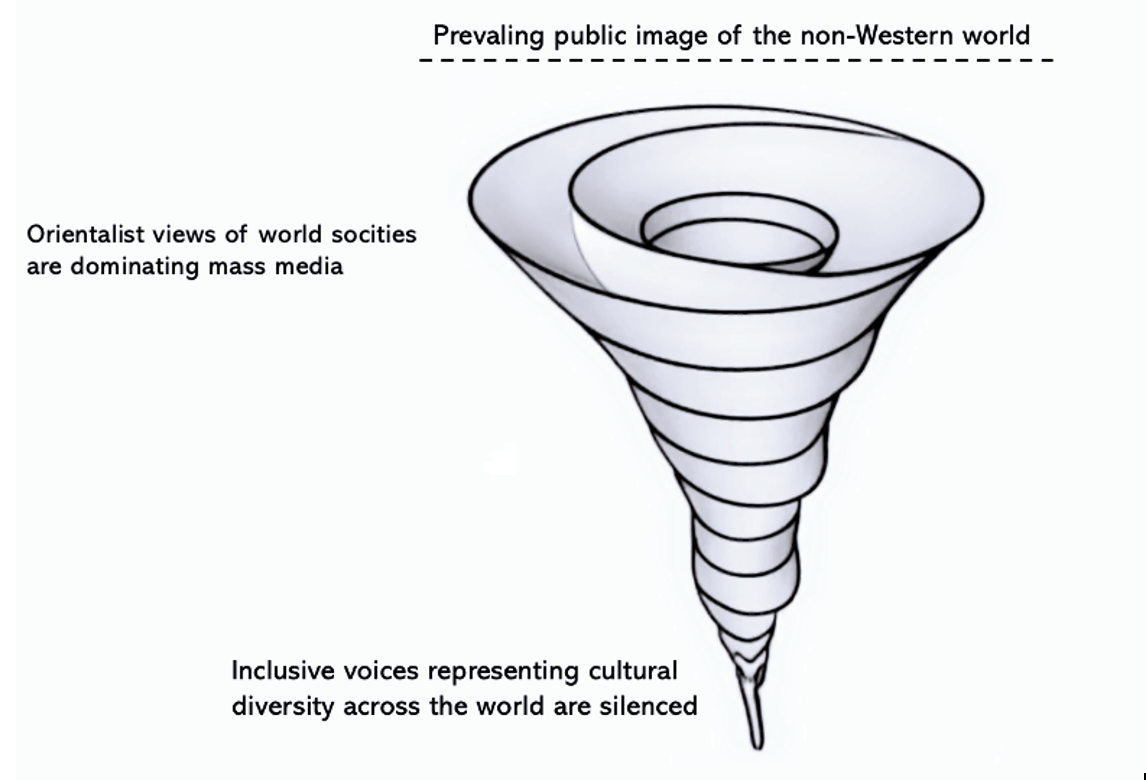

In the Spiral of Silence, people remain silent when their opinions are in the minority. According to Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann (1974), the fear of isolation influences public opinion expression. An individual’s perception of the macro-group opinion affects their willingness to express their views and may lead to communication apprehension. The process of the Spiral of Silence is dynamic, and public opinion acts as a medium of social control. It begins with people’s desire to fit into their society and avoid isolation. When the majority is vocal and their perspective is reinforced through mass media or interpersonal relations, the minority opinion is pushed back and becomes silent.

Noelle-Neumann pointed out that mass media could skew public opinion and lead to widespread "pluralistic ignorance." The media plays a major role in creating dominant views within a social environment, thereby determining the climate of public opinion. People tend to align their opinions with the media’s selective portrayals, which downplay some perspectives, while amplifying others. Indeed, this could lead to people accepting and conforming to certain views, which shape societal norms and values and ultimately constitute social change. The media can be a powerful tool in leading public opinion on new topics. The behavior of social media users depicts the Spiral of Silence in their avoidance to speak within a homogeneous social network where people are familiar with each other and could be afraid of being isolated, ostracized, or rejected.

Tested and confirmed in political elections in Western individualistic cultures, this phenomenon is also observed in Eastern collective cultures, where people’s attitudes toward communicating their perceptions are shaped by the social norms and principles of the majority groups. In both cultures, possessing—or lacking—specific personality traits and individual characteristics such as extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, openness to experience, hardcore, decision behavior, and interpersonal communication are directly linked to people’s moral behaviors in expressing their views within what they perceive as an unfriendly opinion climate.

Gender interplays with socio-cultural contexts in the Spiral of Silence. Evidence suggests that women tend to self-censor and avoid criticism in male-dominant situations, thereby suppressing their views. When traditional gender role stereotypes are dominant, they may contribute to silencing women on topics related to non-traditional feminism. Moreover, women tend to voice their opinions when they perceive public social support in issues related to feminism and gender equality. However, they may avoid speaking in discussions related to leadership and power structures when they feel they are in the minority. Women with multiple identities within minority and marginalized groups, such as disadvantaged women of color, may experience greater fear of social sanctions. Women on online discussion forums can be anonymous and thus may be less likely to experience a fear of rejection. However, evidence shows that women may encounter greater online harassment when sharing their minority opinions.

In conclusion; in line with the theory of the Spiral of Silence, the voices and perspectives of reality in non-Western cultures are overruled by a macro-group of Orientalists. The presentation of ‘other’ cultures is subdued by Western mass media outlets, resulting in the formation of rigid, categorical images of the non-Western world. Contrary perspectives, which may depict the social realities of cultures across the globe, do not blend in the public opinion climate, where people are preconceived through dominant narratives. An exception to the Spiral of Silence exists in two types of groups: the hardcore nonconformists and the avant-garde. The former refers to individuals who have experienced rejection due to their beliefs, while the latter includes the innovative and forward-thinking individuals such as intellectuals, artists, activists, and reformers. The avant-garde, in my opinion, has the potential to bring together diverse perspectives representing all groups inclusively and subsequently inform and provide more inclusive globalization and conveying the true reality of world societies.

Date: 28/02/2025

References:

- Mirrlees, T. (2013). Global entertainment media: Between cultural imperialism and cultural globalization. Routledge.

- Shabir, G., Safdar, G., Jamil, T., & Bano, S. (2015). Mass Media, Communication and Globalization with the perspective of 21st century. New Media and Mass Communication, 34, 11-15.

- Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

- Gillis, C. (2000). Postmodernism and the Other: The new imperialism of Western culture. Islam & Christian Muslim Relations, 11(1), 132.

- Shaheen, J. G. (2003). Reel bad Arabs: How Hollywood vilifies a people. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social science, 588(1), 171-193.

- Al-Absi, M. (2018). The concept of nudity and modesty in Arab-Islamic culture. European Journal of Science and Theology, 14(4), 25-34.

- Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974). The Spiral of Silence: A Theory of Public Opinion. Journal of Communication, 24(2), 43-51.

- Drew, M. (2022). Expanding the Scope of the Spiral of Silence Theory to Increase Relevance in the Digital Age. Journal of Student Research at Indiana University East, 4(1), 104-124.

- Sohn, D. (2022). Spiral of silence in the social media era: A simulation approach to the interplay between social networks and mass media. Communication Research, 49(1), 139-166.

- Huang, H. (2005). A cross-cultural test of the spiral of silence. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 17(3), 324-345.

- Lee, W., Detenber, B. H., Willnat, L., Aday, S., & Graf, J. (2004). A cross-cultural test of the spiral of silence theory in Singapore and the United States. Asian Journal of Communication, 14(2), 205-226.

- Nam, K. (2010). The Effect of Personality on the Spiral of Silence Process. 26(2), 365-388.

- Kartalis, Y. Who breaks the online Spiral of Silence? Users’ personality behind social media political expression in Spain.

- Dashti, A. A., Al-Abdullah, H. H., & Johar, H. A. (2015). Social media and the spiral of silence: The case of Kuwaiti female students political discourse on Twitter. Journal of International Women's Studies, 16(3), 42-53.

- Di Lellio, A. (2016). Seeking justice for wartime sexual violence in Kosovo: Voices and silence of women. East European Politics and Societies, 30(03), 621-643.

- Kramarae, C. (1981). Muted group theory. In M. M. B. Orbe (Ed.), Communication in personal relationships (pp. 52-66). Pearson Education.

© Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.